For several weeks I’ve been musing on the concept of new aestheticism, thanks to a particularly gripping talk Justin Hodgson gave at our Institute for Digital Arts and Humanities meeting in late March. Hodgson outlined new aestheticism for those of us in the room new to the concept (as I was). Originally (and loosely) defined by James Bridle, new aestheticism captures a sense of beauty that emerges from algorithmic culture. Other big names in digital art and new media (Bruce Sterling, Ian Bogost) have built on Bridle’s term, either working to focus it by categorizing particular principles of new aestheticism, or embracing the “weirdness” of digital environments and frameworks to extend its boundaries.

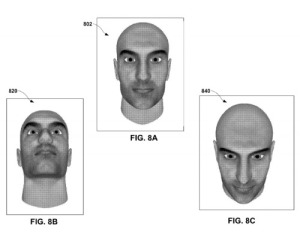

Post from Bridle’s “The New Aesthetic” tumblr on Google’s work on facial passwords (September 2013).

After declaring that the new aesthetic phenomenon has “resisted categorization,” Hodgson attempted to categorize it—but not by outlining a set of principles that describe the movement’s objects. Instead, he argues, new aestheticism is always inherently tied to the way humans are making meaning from and relating to technology. Hodgson’s categorization, then, defines the term not through the elements of the objects themselves, but through the relational frameworks new aesthetic objects reveal. To take this one step further, Hodgson seems to be defining the new aesthetic as an experience that reflects on the experience of digital and new media engagement.

The concept of new aesthetics, and Hodgson’s very useful definition of it, resonates directly with my dissertation work, which thinks about form, mediation, and intimacy in early modern poetry and drama. As a framework for my project, I turn to early modern anatomy and the struggles early anatomists faced as they worked to represent emerging knowledge of the body. These struggles circle the questions of form, mediation, and intimacy at the heart of my project, and connect in interesting ways to new aestheticism. As I’ve delved deeper into my project over this past year, I’m increasingly struck by the connections between questions raised by early anatomists and the questions digital humanists raise about our relationship to digital and new media environments.

My digital work considers how the body engages with digital data, and I look to projects like DataPLAY (Vibrant Lives team) and emoto (Studio NAND) as models for these questions. These projects are related to Bridle’s concept of new aestheticism in a lot of ways, especially Hodgson’s reworking of the concept: thinking about how humans make meaning from and relate to technology. To connect this idea directly to early modern anatomy, early anatomists like Andreas Vesalius, Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, and Charles Estienne were thinking about how humans make meaning from and relate to the insides of our own bodies. And, at the time, anatomical techniques were an emergent technology, uncovering for the first time the internal body as a system that could be interacted with, learned from, studied, and felt.

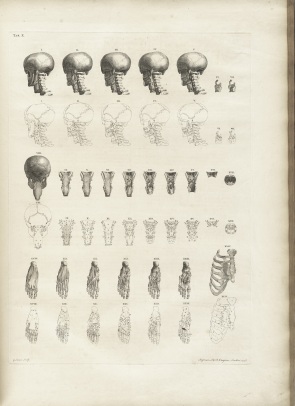

There are important links to the work of early modern anatomy that I think can help us further theorize the concept of new aestheticism. Viewing new aesthetic images and objects “is like solving a puzzle”—these environments “elicit the analytic side of seeing” and ask us to analyze and decode the relations they portray (James Elkins, Pictures of the Body: Pain and Metamorphosis 25-26). Similarly, the trend in early modern anatomical texts was to work toward an ordered and systematic representation of the body. As anatomy evolved through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it became increasingly concerned with schematization and effective knowledge production. James Elkins beautifully traces this trend in his Pictures of the Body, arguing that anatomical and medical texts increasingly (all the way into our current moment) “have to do with the density and arrangement of information, rather than the meanings of the images as representations of the body” (Elkins 128).

Image courtesy of “Historical Anatomies on the Web” through US National Library of Medicine.

As early modern anatomy developed, images like this one from Albinus’s Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani (1747) emerge—a new system for schematizing the body and its parts, organizing the interior of the body as a set of indexes. Each tiny body part can be pointed to, and the reader gains knowledge of the body through each part’s indexical function. This is the analytic side of seeing the body that we can map onto new aestheticism. New aestheticism takes up questions of bodies and digital environments in ways that are schematized, analogical—its images, and the bodies interacting with digital platforms within the images, center on processes of decoding in order to find meaning in the relation between body and technology. In anatomy, the body is at the mercy of scientific technology and the technology (the science) increasingly gains momentum, meaning, and new techniques through its interaction with the body. In the same way, new aestheticism allows us to gain insight about and ask new question of the technology we’re interacting with on a daily basis.

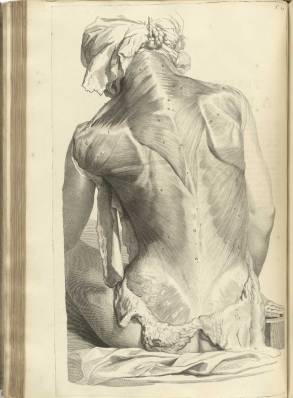

From Bidloo’s Anatomia Humani Corporis (1685). Image courtesy of “Historical Anatomies on the Web” through US National Library of Medicine.

More crucially, though, both movements help us make new meaning through our bodies, and here, I think, is where the limits of both movements reveal themselves. As anatomy became increasingly schematized, the body emerged as a mechanic system with parts that functioned in different ways—anatomical images gradually “represse[d] the complicated and unsettling presence of the opened body” (Elkins 128). In other words, anatomy lost touch (pun intended) with the bodiedness, the somatic, material stuffness of its bodies. On the margins of the schematizing trend in early modern anatomy was the work of Govert Bidloo. Bidloo’s work didn’t catch on in the same way as Vesalius and Albinus’s because Bidloo paid too much attention to the body in pain. Bidloo’s plates were never schematized or organized into numerical keys and indexes—he focused on the realistic representation of a dissected body and its parts, to the point where the reader feels the pain of the dissection process.

New aestheticism provides a way for us to think about how our bodies relate to technology—as Hodgson claims, a way to explore how humans are making meaning from digital engagements. And it is, of course, important and compelling to learn more about technologies and our relations with them. But the problem emerges when we start thinking about those relations purely within the terms and discourses of the technology, when we start to schematize and organize our bodies in relation to the technology’s dictates—and this is what the new aesthetic reveals. We accommodate the technology into our bodies, and allow it to dictate how we use our bodies in relation to it, rather than forcing the technology to accommodate our bodies and the messy, complicated, singular material stuffness of our somatic makeup.

Like Bidloo’s attention to the messy collision of anatomical technology and body, can we use new aestheticism to consider the moments of disconnect between bodies and technologies? Not necessarily as a way to explore the meaning of our interaction with digital environments, but rather as a tool for recognizing how our bodies are forced into certain interactions with the digital? And, from there, can we turn to moments where the body refuses to be incorporated into or somehow incorporate the new media? Can we use new aestheticism to explore instances where meaning finds its limit point in the interaction between body and technology—moments where meaning actively cannot emerge?